maison ikkoku: my life in the house of jerks

originally posted: 8 june 2015

Gen-Z weebs, you don't know how good you've got it. Back in the heady days of the early 1990s, anime and manga were pretty hard to come by in the midwest. I had to take what I could get, which was mostly released by Viz, and mostly expensive. With only a limited amount of spending money, I often stuck with what I knew—and what I knew was that I loved Rumiko Takahashi. After devouring all the Ranma 1/2 I could, I fell in love with the bawdy interstellar antics of Urusei Yatsura, and terrified myself with existential dread and body horror of the Mermaid Saga.

And then there was Maison Ikkoku, a comics series that obviously wasn’t aimed at pre-teen American boys. I didn’t fully understand it, but I still managed to enjoy it, much to the bafflement of my friends.

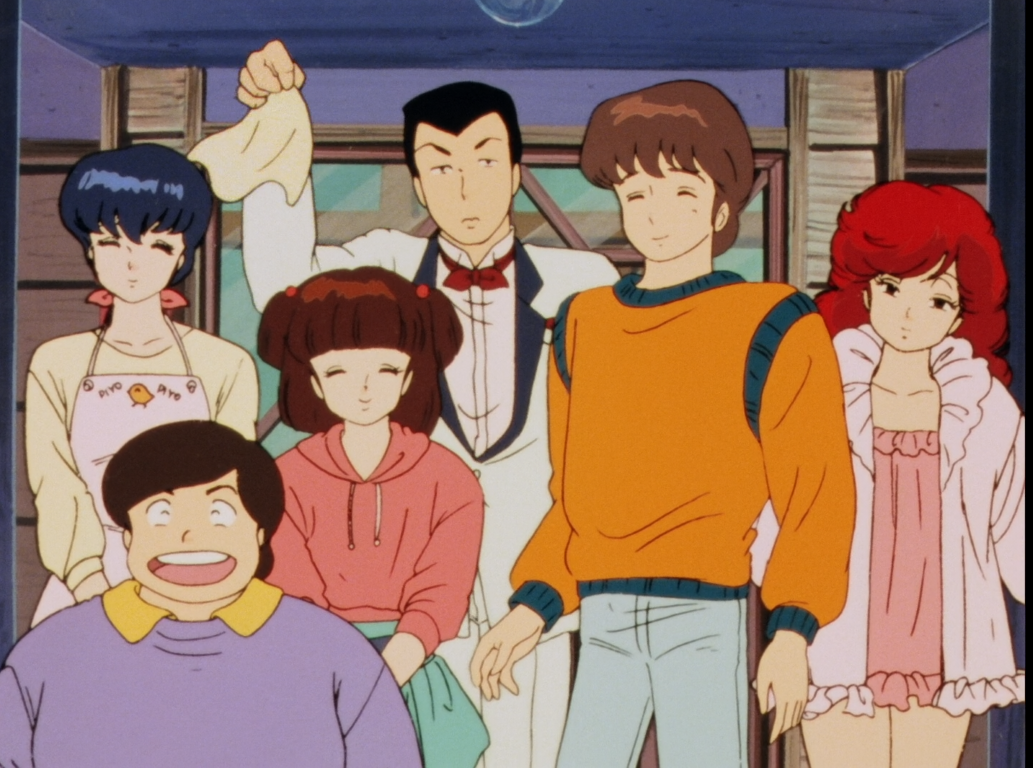

Running from 1980-1987, Maison Ikkoku is the story of depressed 20-year-old rōnin Yūsaku Godai who, too embarrassed to return home after failing his college entrance exam, moves into the eponymous boarding house in an effort to cram and re-take the test the following year. Ikkoku-kan is populated by an odd bunch of characters who constantly intrude on Yūsaku’s life. Staying in Room 5, Yūsaku is sandwiched between the polite pervert Mr Yotsuya in Room 4 and Room 6’s lackadaisical cocktail waitress Akemi Roppongi. Below them in Room 1 lives middle-aged lush Mrs. Ichinose (get it, each tenant's room number corresponds to their surname) along with her rarely-seen salaryman husband and their young son Kentarō. The tenants regularly descend on Yūsaku and invade his room, drinking and partying all night while he’s trying to study, and eating all of the food from the care packages his doting grandmother sends him. He’s not pleased about the situation, but he’s too much of a pushover to do anything about it.

Rounding out the residents is Ikkoku-kan’s caretaker Kyōko Otonashi, a young widow who Yūsaku’s head-over-heels for. Despite the fact that she obviously has a bit of a thing for him too, he just can’t seem to tell her how he feels. Kyōko is joined by her big samoyed Mr. Sōichirō, named for her late husband, a character who looms large (like a samoyed) despite his absence.

A fairly straight-laced romantic comedy, the unresolved romance between Yūsaku and Kyōko serves as the crux of Maison Ikkoku’s story. Its characters, while often hysterical, are far more grounded than those found in other popular manga of the era. Their character designs reflect this, featuring none of the outrageous outfits or hair colors found in Takahashi’s other works in favour of contemporary 80s fashion.

This all sounds like a solid enough concept for a manga or anime, but it’d make for an unlikely video game. Despite this, those underrated geniuses at Micro-Cabin saw fit to rise to the challenge, creating a Maison Ikkoku ADV that first released for microcomputers in 1987 before receiving ports to the PC Engine and Famicom in 1989. For the sake of my inadequate Japanese skills, we’ll be looking at the PC Engine version, which was fan-translated in 2008 by Matthew La France and David Shadoff.

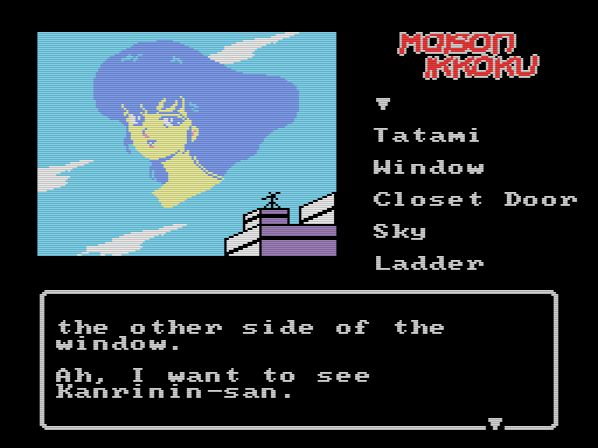

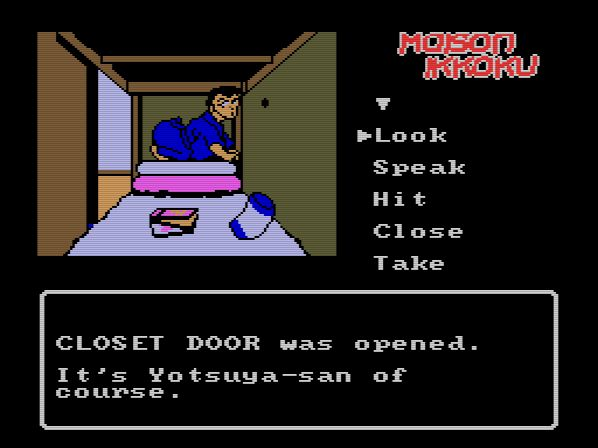

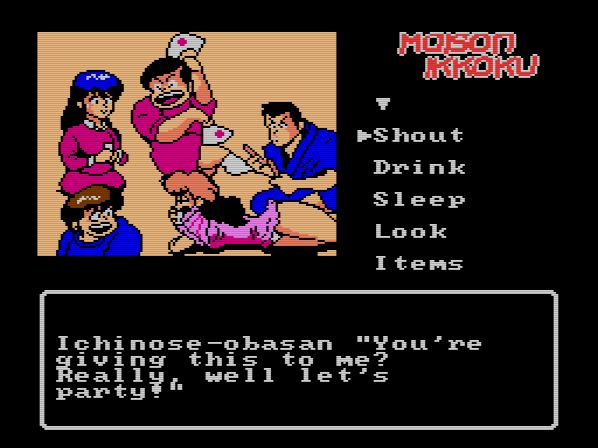

Maison Ikkoku puts players in the position of Yūsaku who, upon hearing that Kyūko has a secret photograph, immediately goes out of his way to find a chance to see it. The game leaves its concept in the instruction manual and wastes no time by dumping you unceremoniously in Room 5. From here, you’re free to explore Ikkoku-kan at your leisure. You can check in on your neighbours, up to their expected tricks: Yotsuya is using a hole in Yūsaku’s closet to peep on the scantily-clad Akemi while she sleeps, while Ichinose is on the shakedown for a bottle of booze. Kyūko is minding her own business in her room, while Sōichirō sleeps in his doghouse outside, accompanied by a listless Kentarō.

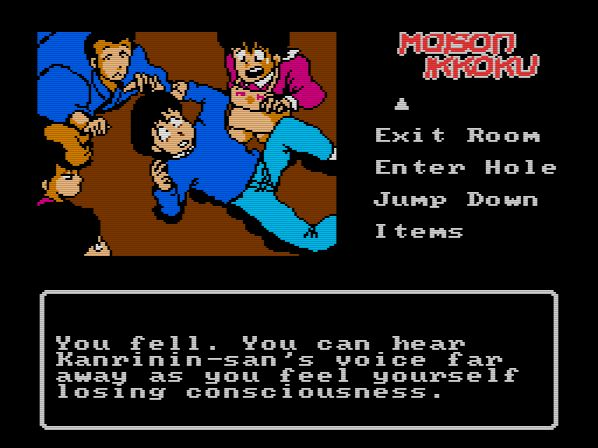

Notably, you can get a game over within the first ten seconds: Yūsaku, ever on the edge, has the option to end it all by leaping from his (first floor) window, suffering a non-fatal back injury that puts him out of commission. Grim enough on its own, it doesn't help that the command “jump out” stands proudly at the top of the verb list in any room with an open window, when out on a balcony, or atop the roof. Hang in there, Godai!

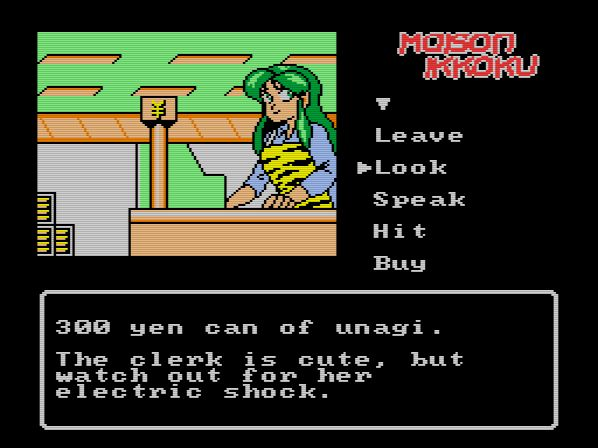

Our first task is to be invited into Kyūko’s room for an opportunity to view her photograph, but this is easier said than done, as Yūsaku’s housemates are sure to get in his way. A core tenet of Maison Ikkoku is the fact that you have to constantly bribe Yūsaku’s housemates in order to get anything done or suffer the consequences. Often these are rather benign, such as Ichinose refusing to leave you alone with Kyūko, while other instances can be game-ending, such as being locked on the balcony or stranded on the roof by an irate Yotsuya. You can get these goons off your case by giving them any number of food items purchasable at the supermarket, or sake purchased at the Chachamaru Bar.

Even after you’ve gotten everybody to leave you alone, you need to buy flowers to present to Kyūko for a chance to be invited in. All this purchasing is made more complicated by the fact that money is a finite resource in Maison Ikkoku. Reflecting Godai’s status as a poor student, he begins the game holding ¥5000. There's opportunities to request a small number of loans from Yūsaku’s various friends, and you can receive a fee for tutoring Kyūko’s niece Ikuko late in the game, but the player is forced to carefully consider their purchases and gifts, lest the game end up in an unwinnable state. Many of the items are expensive red herrings, and often buying cheap ramen works just as well as a bribe.

The first time you gain access to Kyūko’s room, your chance violate her trust is interrupted by Akemi, requesting that Kyūko come and repair the bathroom door. With that, the cycle repeats; bribe your housemates to leave you alone, give Kyūko flowers, and get kicked out by another neighbour with terrible timing. This happens three more times, until your final task is to collect photos of the other tenants to show Kyūko in exchange for a peek at hers. The game gives little direction on how to achieve this series of obscure goals.

Maison Ikkoku, unlike many of its ADV contemporaries, cannot be brute-forced through exhausting all of your verbs. Managing your fellow tenants' hierarchy of needs has a puzzle aspect to it, but the solutions are so poorly communicated that the game quickly becomes an exercise in frustration. It’s also quite easy to work yourself into an unwinnable state: For example, after being forced to visit Kozue—Yūsaku’s situationship—and her family, Kyūko, in a fit of jealousy, will refuse to speak to Yūsaku. She can be placated by returning her bra, which blew up on to the roof. That’s all well and good, unless Yūsaku is forced into visiting Kozue a second time. With no bra to give back, I couldn’t find a way to placate Kyūko, and had to enter a 67-digit (!!) password to reload an earlier save. No battery backup here, folks, and it aches.

Gameplay faults aside, Maison Ikkoku's pretty attractive for a 1989 Hu-Card release, doing an admirable job of recreating Takahashi’s unique character designs. The music is particularly lovely; the relaxed theme that plays within Ikkoku-kan will certainly stay with you long after you finish the game. The visuals and audio work together to evoke a sense of melancholy that is right at home with the manga’s theme of a penniless student struggling with unrequited love (creepy, photo-stealing invasions of privacy, notwithstanding).

Most importantly, Maison Ikkoku provides a rather intimate portrait of the source material’s world. Exploring Ikkoku-kan from top to bottom, interacting with its tenants, and even the minutiae of supermarket shopping and tutoring a child; all of these actions serve to immerse in the world of Maison Ikkoku, something that is arguably more interesting and valuable than the completion of the game’s tasks. Even dealing with the pesky tenants, shallow as it can be, succeeds in making you feel like the put-upon Yūsaku. This type of intimacy is something you don’t often find in video games based on licensed properties, and it’s quite charming.

There are overt hints of an avant garde experience here. I can only imagine how this ADV could have turned out if Micro-Cabin had decided against playing it safe, eschewing the goal and endpoint in favour of something more akin to a slow-life adventure that took place in Maison Ikkoku’s world. Hey, it could work.

Micro-Cabin released a microcomputer-exclusive sequel in 1988 called Maison Ikkoku: Kanketsuhen (“The Final Chapter”) which follows the last few volumes of the manga up to its conclusion. English information is scant and second-hand copies are hard to find, but it appears to be more akin to a linear VN than its predecessor. I hope to give it a look if I can get my hands on it someday.